POINTE-A SIGN EXHIBITION 2021

Text about Ineke Domke's bachelor's degree

June 24, 2021, Rotenburg Art Association

Speech on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition “Pointe - a drawing exhibition” by the artist Ineke Domke.

The speech was given by Professor Michael Dörner. And now follows:

To the audience,

art club members,

Hello everyone,

Hello dear Ineke,

As always, it is a happy event when we can say goodbye to a bachelor's graduate. As always, it's also sad because we usually lose sight of them. If we as a university didn't invite people to meet up every now and then, contact would probably be lost entirely, which is a real shame. Because both sides, at least I hope, benefited from this time together. Ineke seemed to particularly like it at our university. After all, she has studied with us for 8 years now. She first studied with my colleague Professor Jochen Stenschke and then received further input from me. It's hard for me to judge whether it was as much as she might have expected, as she came into my class as a very good draftsman. I will miss Ineke very much in the class, as she was always actively involved in all the discussions. Everything she said had substance and there was always a certain maturity and serenity about it.

Now she has taken the leap into normal life, i.e. the “life that no longer wants to be a student”. That doesn't have to mean that she's no longer studying, or better, as they say in the artistic profession today, that she's no longer doing research, but it has to mean: Now it's really getting started! Just without the constant support of lecturers and fellow students. Yes Ineke you did it and as expected it was really good.

You were very lucky with the location here, as almost all exhibition spaces, galleries and museums were closed during the pandemic. I would therefore like to thank once again and again the Rotenburg Art Association and, in person, especially Peter Mokrus, who is particularly connected to our university. There have been numerous projects and exhibitions here in this wonderful tower. So let's be happy that we can stand here together today and look at Ineke Domke's exhibition.

Now it is the case that my esteemed colleague Hermanns Westendorf, who unfortunately passed away, left us an inheritance that is, on the one hand, very nice, but on the other hand also represents an obligation for us lecturers in the fine arts course. The farewell of our students is always accompanied by a final speech, which is intended to introduce the presentation of the exhibition and also represents a laudatory speech for the graduates. As is currently the case when we are burdened with a lot of tasks, this can also lead to the last little free sliver of time being robbed from us. In moments like this I curse this legacy.

On the other hand, I'm happy to hear that the final speech is something that means a lot to the students.

But then again you hear people say: “I won’t come to an exhibition until the talk is finally over.” Just as if it were annoying to have to listen to what nonsense the speakers had come up with. “I don’t need anyone to explain art to me.”

So, I think to myself, I'll just leave it alone, go home now and see what happens.

That's not funny, I hear some people saying in my head. No, that's really not funny. But what's funny?

Break…

So I'll just stand here and do whatever I want.

Last but not least, it's a little fun to work intensively on the work again.

I usually start with the title.

But what's the punchline? If the punch line doesn't come at the end, the command for everyone is: please laugh now?

But then I would have to start from the back with my entry. But who starts with the punch line and then tells the rest of the story.

As usual, I'll first check what the punchline means. Wiki has to come first.

The pointe, which comes from the French tip, has its origins in the Latin puncta, the line. “The punch line is a name for a surprising final effect as a stylistic figure in a rhetorical sequence. The comical and witty effect of the punchline is based on the sudden realization of meaningful connections between mismatched concepts. Something like the actually unexpected meaning. As a rule, the appearance of the punchline is formally precisely programmed through the rhetorical construction and is sometimes predictable”1.

Does the artist anticipate the punchline by calling her exhibition Punchline? Or are we attaching excessive importance to the subject of the punch line?

As it says on Wikipedia:

“The meaning of punchline can now only be understood because it was understood - following Aristotle - as a product of perceiving similarities between different objects. This gave the punchline an almost epistemological status.”2

I let the last sentence melt in my mouth again. So slowly again:

- as a product of perceiving similarities between different objects

I think that's what the artist is getting at. That is clearly visible. She uses the oldest and simplest artistic means of expression. The most prominent features of the drawing are the line and the point. With these two elements, almost anything can be represented.

No matter what specific purpose or function a drawing has, it always embodies a spiritual principle in the visual arts. “As a direct implementation of a picture idea, it can be carried out at any time and anywhere and is therefore the most intellectual part of the creative process that is most closely linked to the idea.”3

Every child knows how easy it is to doodle on a rock with a piece of charcoal or to write in the sand with a stick in your hand. The works of Ineke Domke in this exhibition show us what possibilities there really are in this medium.

By the way, she is not the only artist who devotes herself exclusively to this medium. Jorinde Voigt, Ralf Ziervogel, Hanne Darboven, Agnes Martin and many more come to mind.

In a drawing, thought and action are inextricably linked. But it was only in the twentieth century that the line, the spot, the grid and the ornament, as well as the word, became formal and conceptual instruments in order to attribute to drawing much more than just a depiction or construction character. The list of means of drawing is long.

We all draw and even writing is - according to Joseph Beuys - a sign.

Every small shopping list or casual telephone doodle can take on graphic meaning. At least it seems that drawing is treated almost inflationarily as an artistic medium.

Only rarely is there a pure draftsman among the artists. All artists draw on the side. It seems like the drawing is an inferior product. Something like the preliminary stage to the actual work of art. The artists mentioned above prove that this is no longer the case. Ineke Domke sees it similarly.

She has dedicated herself to the art of drawing and draws as much as she can. At the beginning she passed her time by adding pure tally marks to pages of large-format sheets of paper, but over the years she has acquired a huge repertoire of possibilities for mixing the individual processes and techniques in such a way that we can no longer stop being amazed come out. She now roams through all media and disciplines, like a woman who knows her way around wherever this linear-two-dimensional technique is used. The formats it can handle range from very small papers to meter-long strips of paper. It is glued, copied, drawn on again, scanned, printed out again and further work is carried out. This creates a procedural work that is miles away from the original starting point.

She repeats motifs, reflects them and reassembles them ornamentally. The rhythm that emerges almost seems like a musical score. A bit like the rhythm of a techno beat and perhaps manages to put us in a trance-like state. If there weren't always motifs that point us back to the actual origins of their origins.

There is a lot of enthusiasm in these works, a lot of love and appropriation, a lot of affection. The need for order in the great chaos of the world of drawings is obvious. And yet, especially in the small drawings, she shows the absolute love of detail combined with the generosity of the lines. The colored line or sometimes small placed areas testify to variations that break the monotonous harmony. It is incredible how confidently Ineke Domke moves in this field of lines, patterns, ornaments and symbols.

During my first visit to the construction phase of her exhibition here in the tower, which was not yet fully assembled, we both talked about her relationship to the copy. A lot of things then went through my head, although copying and reproducing is a common process, there are still a lot of legal disputes regarding this process.

However, when artists consciously and strategically copy other artists' works, we no longer actually speak of plagiarism or forgery.

Since Appropriation Art was introduced with the exhibition “Pictures” (at the New York Artspace in 1977, curated by Douglas Crime), we have recognized the engagement with the processes of appropriation and assimilation, of quoting, rewriting, revising, paraphrasing. We know how it works with interpretation, imitation, parody, piracy and mimicry.

Ineke Domke does exactly that and yet it is not appropriation art. She has no problems with authorship, originality or intellectual property. Because much of what it uses is freely available or is changed in such a way that the origins can no longer be recognized or traced.

In approbation art, we as viewers should definitely recognize the references and quotations that are used and include the interpretation and knowledge about them in the new reception situation. Things are a little different with Ineke Domke. Her quotations or robberies never refer to the meaning of the works of individual artists or genres, but rather to the actually truly perceived phenomenon, which she hermeneutically pursues.

When understanding, people use symbols. Some vast world of signs surrounds us and helps in understanding and communicating. Understanding something means approaching a text, a conversation partner, or even a work of art with a concrete expectation and then constantly revising this as we penetrate the other person's mind.

So understanding is a kind of application to a situation. The application involves an argument through questioning. Actually, we can also understand the meaning separately from the artist's intention. Seen in this way, her approach is a kind of reflection on what happens to oneself in one's own dialogue: understanding oneself through understanding the work of art.

Ineke Domke, in keeping with Hans-Georg Gadamer (-insiders may have already heard it-), succeeds in this hermeneutic effort wherever the world is experienced and unfamiliarity is eliminated, where enlightenment, insight, and appropriation take place, and in the end also there, where the integration of all scientific knowledge into the personal knowledge of the individual succeeds. Gadamer also emphasizes the opportunity to use the temporal distance between the viewer and the object of the tradition productively: I quote: “But the exploitation of the true meaning that lies in a text or an artistic creation does not come to an end somewhere, but is actually an endless process. Not only are new sources of error constantly being eliminated so that the true meaning is filtered out from all sorts of clouds, but new sources of understanding are constantly emerging that reveal unexpected connections to meaning. The time interval that provides filtering does not have a closed size, but is in a constant movement of expansion.”4

I think it's an absolutely exciting idea - continually perceiving and recognizing new sources of understanding, which have come about over time, not as a loss of historical knowledge, but as a constant gain.

Dear Ineke, I always enjoy looking at your drawings. Every new look at it always brings me new discoveries and insights. I thank you for this.

Now my “I do what I want” has made sense, but still no point. I won't be able to do that today either. But I would like to get rid of something else that perhaps doesn't belong here at all, but is still at least perceived as something by me so that I remember it.

A few years ago, we were on an excursion in Düsseldorf, it was hot and I probably noticed your tattoos on your arm for the first time. I asked about it and you talked to me about it. I don't remember the exact contents, but personal information was included. I was impressed by the conviction with which you presented the intentions and meanings of the motifs. Although I believe that these motifs never have anything directly to do with the motifs in your drawings, I see a parallel in the manifestation of the line and the intention behind it. The tattoo itself is very old and there are many cultural references to the modalities. Tattooed skin only appears much later in Western art. I would like to recall just a few examples here, such as the garter tattooed on Valie Export's leg (1970) as part of a public event, or the tattoos a year later on Tim Ullrich's "first living work of art" (1971). Also interesting are the tattooed pigs by Wim Delvoye (since 1997) or the tattooed back of the Swiss Tim Steiner, who exhibits himself as a living work of art in numerous museums. The Hamburg gallery owner and collector Rik Reinking even paid €180,000 for it.

The list could now go on forever. Tattoos have now arrived everywhere. Also in art.

Art gets under your skin. Ineke Domke's drawings are complex. They penetrate through the surfaces and into the deep world of symbols. So let's go on a dive and, in the spirit of Kadaver, get involved in understanding ourselves through understanding the works.

Ineke, as always, traditionally gives you a quote at the end.

This time by someone else, the artist Thomas Bayerle. I can't help it, but it's somehow present when I look at your works:

“If everything happens at the same time, possibly in the form of this “lemonade mixed media,” then no one can concentrate anymore. You only worry about warding off headaches. But there is also the moment of the highest “happy condensation”, which can be understood as a total opening, even as “calm in the frenzy”. At this moment - when things are going well - different components do not conflict with each other, but rather add up to create a new quality. To that totality that can be found in Joyce, Prout, or other masters.”5

Prof. Michael Dörner, June 24, 2001

1https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pointe

2ibid

3Julia Klüver, Hans Peter Wipplinger Foreword to the catalog “Forinte Voigt - Now”, published by the bookstore Walter König, 2016, p.6

4https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermeneutics

5Thomas Bayerle, Der Städel, Frankfurt ed. By Sabine Schulze, exhibition catalog 2002, p.113, ISBN: 3-934823-98-0

Manuelle Zeichnung auf Digitaldruck, 2019

2019

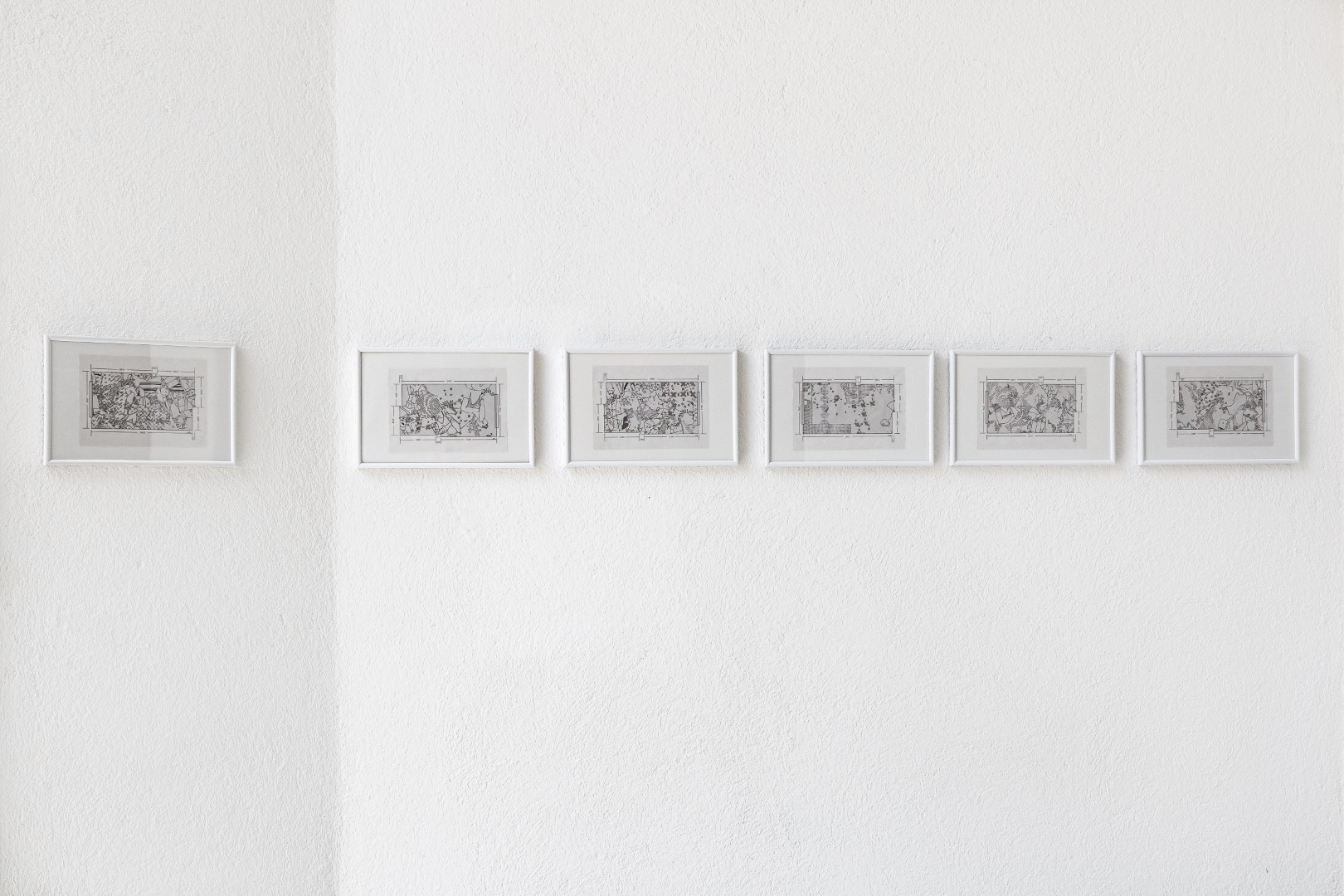

Serienausschnitt Kunstturm Rotenburg, Digitaldruck vom Raumgrundriss des Ausstellungsortes und Zeichnung mit Pigmentmarker auf Transparentpapier, 2020.

2020

Serienausschnitt Serie Level One, Digitaldruck vom Raumgrundriss des Ausstellungsortes und Zeichnung mit Pigmentmarker auf Transparentpapier, 2019.

2019